I’d like to use a sports analogy to explain how I feel about the changes to the writing assessment.

Imagine you had been training for the Rio Olympics to be held in the summer of 2016. You could be a high jumper for example. The qualifying height for Rio ’16 is 2.29m (men). So, imagine you are that high jumper and you hit your target again and again and again. You feel like you are ready for qualification. Ready for Rio. But a few months before, there are rumours that the bar will be higher for qualification so as an athlete you start to jump higher, training harder and exceeding your personal goals. Once again you feel as though you have cracked it, however four months before qualification there comes a shock announcement from the governing body. As well as jumping 2.29 metres you also have to jump 2 metres horizontally. Now you may think that ‘good’ athletes should be able to jump 2 metres anyway so this should not have a detrimental effect on the athletes. However, for some athletes the original 2.29 metre target was their best. They focussed fully on achieving more height as this was what has always been measured. For these athletes, jumping horizontally is almost impossible as all of their effort has been expended on the original vertical target. So what happens to those athletes who do not meet the new targets? They lose their funding, they are labelled as failures and they feel that all of their training has been for nothing. There are athletes who can meet the new expectations, they cannot see what the problem is, in fact their coaches support the changes as it makes their athletes and themselves look even better than usual. What happens to the coaches of the ‘failed’ athletes? They are put under increased scrutiny and eventually lose their jobs while the governing body touts their positions to the highest bidder. Now imagine that instead of athletes you are a 10 or 11-year-old who has gone through their whole primary school career with one curriculum. This was changed by the government less than two years before testing and the bar was raised. Their teachers heard rumours that the standards required would be higher so they taught accordingly. Then four months before the assessment process the goals were changed. Under the old system some objectives were not put under as much scrutiny as they are now, which meant that in some schools they were not practised as much as there could have been. This could have been for a number of reasons but perhaps all of their energy was expended on reaching that ‘higher bar.’ So now a large amount of our pupils will be labelled as failures, their teachers will be put under greater scrutiny and could possibly lose their jobs when their schools are forced to become academies by the government. In summary, I am all for ‘raising the bar’ but raise it gradually, and then just move it vertically and not horizontally. If you want to move it sideways or even change the bar altogether then give teachers and schools enough time to implement the changes before testing the children and using the results to label them, their teachers and their schools as failures.

6 Comments

As I have said in my previous posts - I am not opposed to testing. I do not like high stakes testing and how the tests are used to judge teachers and schools.

However, I am against tests that are filled with 'booby traps' and questions designed to confound and bamboozle young children. I call them 'trick questions,' but it has been pointed out to me that they are not trick questions just difficult ones. I have come across a few sample SPAG test questions recently that have made me think. The first from the KS1 Sample test.

"We want children to be able to identify verbs in a sentence." says one civil servant.

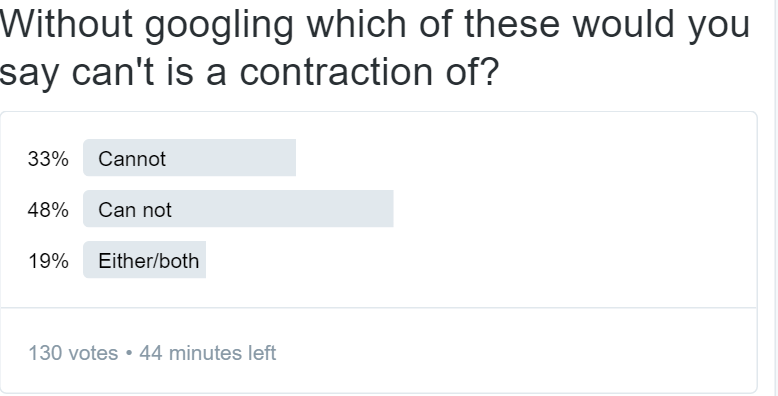

"I agree!" says Morgan "but how can we make it as tricky as possible?" "Let's put them in the past tense and make them irregular!" "Then just to trip those 6 or 7 year olds who may be stressed and flustered by the tests we'll put in an adjective that looks very much like a verb." "Yes, Yes, Yes!" squeals Morgan with delight! "Gotcha!" she shouts, pumping a fist in the air. The second question is from a KS2 Sample test. The question is testing the child's understanding of apostrophes for contraction. So the (un) civil servants designing the tests have lots to choose from. In their question the could ask which words have been contracted to form the following: Shan't, Couldn't, Wouldn't or even Won't which is common but irregular. Which do they choose? One that is the most irregular. Unique amongst its peers. Can't - You may not think this is very difficult. However, Can't is the only* contraction that is formed from a single word. Cannot - no credit will be given if the children write 'can not'. This is grammatically correct but it is again another trap, into which 10 and 11 year olds who have not been exposed to a full and rigorous grammar curriculum, will fall into. I know they will because I carried out a very unscientific experiment. I asked the following question on twitter.

I would like to think most of my twitter followers are well educated adults, most of whom are teachers or within the educational system. However, as you see from the image above only 1/3 of the 130 respondents would be given credit on a Spag test and this wasn't in a highly pressurised timed test.

So 1/3 of adults would have got credit but many schools are aiming for at least 85% of their students getting these correct. Fair? I do not think so. Please share these examples far and wide. Parents of our children need to be outraged by questions like this. Parents need to know how the government are purposely trying to make children fail in their tests. As I always I welcome your comments. Rob *I couldn't think of another one word contraction other than cannot.

Grammar does not need to be taught out of context, it can be taught in English lessons through the use of quality texts. (Quality texts include film, drama and teacher modelled texts) In this blog I will share six steps follow in order to embed grammar into weekly English lessons. This process may take a single session plus the revisit or it may take a number of lessons, this is dependent on the ability of the children and the difficulty level of the task.

The six R’s of Grammar are: Read Retrieve Rehearse Repeat Revise Revisit 1. Read – Reading for enjoyment and familiarisation with the text in the first instance. Allow children to read and and discuss freely without the shackles of ‘grammar spotting. The text does not have to be a written extract at this point. It could be a film or spoken piece. Both of these use identifiable grammar features. 2. Retrieve – Reread the text in order to identify and retrieve the grammar features that are the focus of the session, pupils may want to highlight or underline them. This could be done individually, with a partner or alongside the teacher in a group where necessary. 3. Rehearse – practice using the found grammar as part of a shared or guided write. Pupils may rehearse on whiteboards. This could be done out of context but it doesn’t need to be. For example if the text used in 1 and 2 was The Three Little Pigs and the grammar focus was expanded noun phrases then the children could rehearse phrases such as 'the small, hairy pig,' 'the house was made of soft yellow straw' etc. 4. Repeat – Children repeat this practice in their own writing. It may be prudent to scaffold this into the given task if children are insecure. Teacher could model how to effectively insert it into their writing. 5. Revise – Look through their own writing and that of peers to discuss/check accurate and effective usage of the focus. Teacher could share a different model from that in the ‘Read’ and ‘Retrieve’ sections so that pupils can identify grammar focus. 6. Revisit – For children to become secure the grammar focus needs to be revisited as often as possible. Teachers and pupils may point out the focus in their reading, teachers may ask for contextualised examples in other subjects such as science or history. |

Archives

July 2020

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed