|

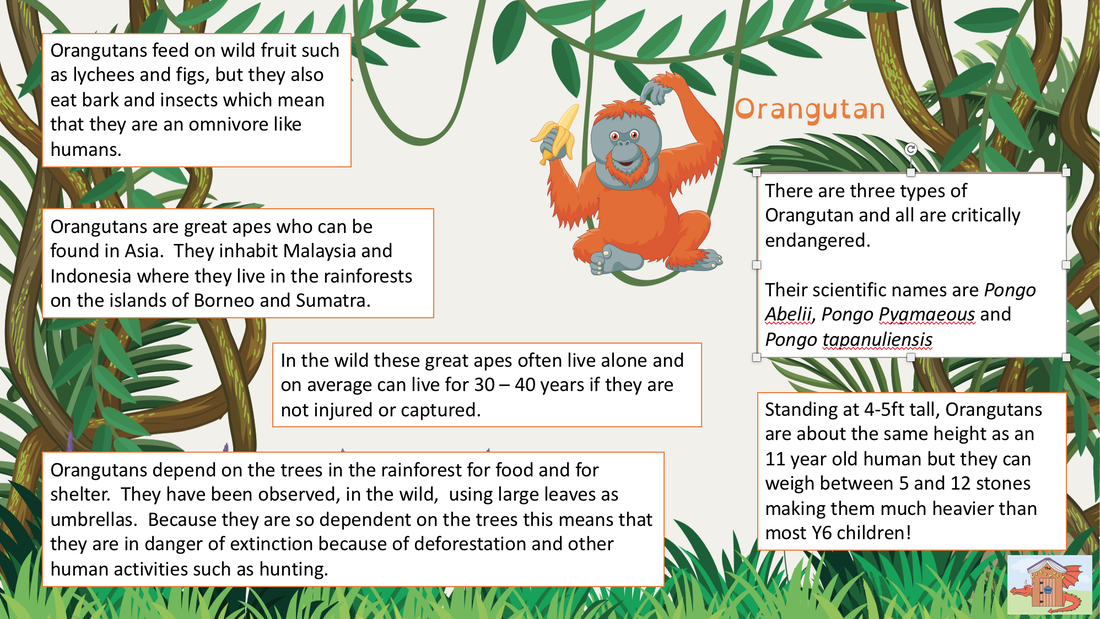

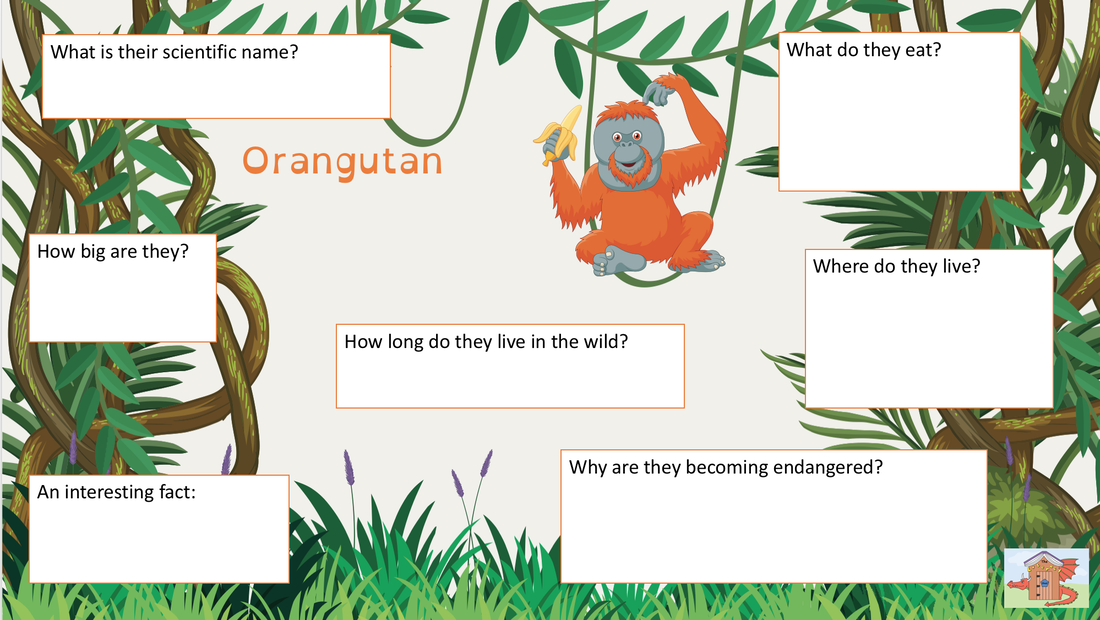

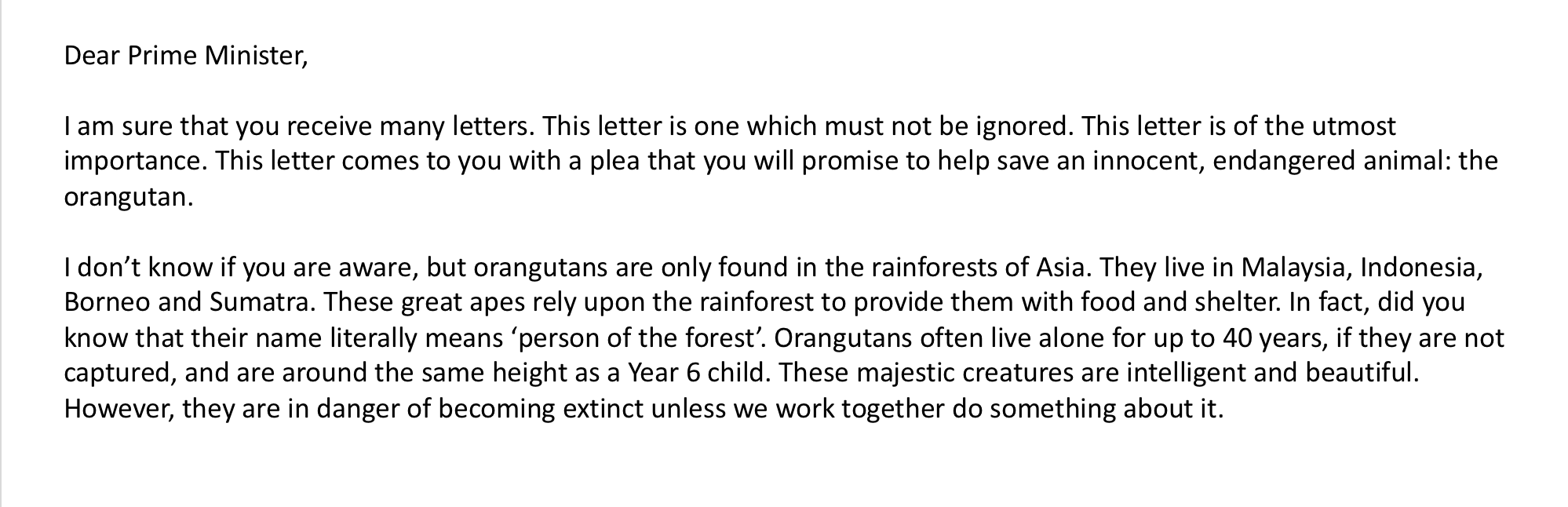

People love to send me films and I have been sent this one quite a few times over the last few weeks. 'Rang Tan' is an educational film made by Greenpeace to educate people about the destruction of the rainforests due to human intrusion, primarily from the Palm Oil manufacturers. These resources are adapted from the great resources that were developed by Greenpeace on the subject. The originals can be found here When using this film with a group of Y4 children this week to tie into their Rainforests topic we began by finding out lots about Orangutans. We began by watching this short film from YouTube. The children then created information sheets about Orangutans using the templates below. The objectives of the lesson here were twofold, the children practise their reading skills in order to find the information but also to improve their knowledge of Orangutans in order to write about them in the following lesson. Before reading, we discussed and contextualised the tricky words from the image below. Click here to download the resourcesIn the next session we watched the 'Rang Tan' video voiced by Emma Thompson and discussed the dual narrative and the story it told. The children followed the text and read along. There are opportunities here for performance, the children could choose a section to perform dramatically. Following the reading sessions, we then decided that we would write letters to the Prime Minister in protest against palm oil products in the UK. This began with a discussion about persuasion. We decided that we should describe the beauty of the Orangutan as in the model below. This would act as a persuasive device as people are more likely to protest for something if they have a relationship with them.

30 Comments

Ask a teacher to name a book about WW2 and they can usually throw around the names of quite a few. ‘The Silver Sword’ (classic one), ‘Good Night Mr. Tom’ (Heart-warming one), ‘Boy in the Striped Pyjamas’ (shocking one) and ‘Once’ (graphic one). Ask though, which of these books describes the setting of a bomb crater the best and less books may be suggested.

It is imperative though, that teachers have a good working knowledge of the texts, the language used and the structures in order to weave them skilfully into English lessons. For this to happen, a wide range of texts need to have been read by the teacher or teachers so that they can recall features, concepts and even sentences which they can use with their students as model texts. Take the examples below, each of them is from a different text but each of them describes a forest. It doesn’t really matter what genre the children are writing; a good description can be utilised across a range of writing episodes. In a hypothetical classroom, somewhere around Year 5 or Year 6, a child is writing about ‘waiting in a forest ready to go into battle during WW2’ based on a picture, film or other stimulus that the teacher has provided. If the class teacher wants to show them a model, they generally have two options – try and find a book where the exact same scenario is occurring (this may not even exist) or write their own model. (Some teachers find difficult). However, much of the language used in the extracts below would be useful, as would some of the sentence structures and techniques such as building atmosphere or using similes. None of the books below are about World War 2 or are from battle scenes though. With some slight adjustments they can be adapted to work for any narrative which needs a description of a forest. The Wizards of Once Perhaps you feel that you know what a dark forest looks like. Well, I can tell you right now that you don’t. These were forests darker than you would believe possible, darker than inkspots, darker than midnight, darker than space itself, and as twisted and as tangled as a Witch’s heart. They were what is now known as wildwoods, and they stretched as far in every direction as you can possibly imagine, only stopping when they reached a sea. Cowell, Cressida. The Wizards of Once: Book 1 (Kindle Locations 32-35). Hachette Children's Group. Kindle Edition. In this description the teacher can discuss how Cowell has directly addressed the reader, used rhetorical devices and repeated the word darker and how this effects the audience. The Dreamsnatcher Tanglefern Forest was vast, with some trees so old and tangled that few had passed beneath their branches. But there were places you went and places you didn’t. The Ancientwood in the north of the forest was safe: there was the glade of brilliant spring bluebells and yews beyond Oak’s camp, then a grove of crab-apple trees, and beyond that, after the forest, the farm itself and Tipplebury village. But south . . . Well, south was another place altogether. So she’d heard. The Deepwood was rumoured to be full of shady trees and rotting undergrowth and, when it ended, the heathland, with it sinking bogs and soggy marshes, began. Elphinstone, Abi. The Dreamsnatcher (Dreamsnatcher 1) (pp. 9-10). Simon & Schuster UK. Kindle Edition. I like in this extract how Elphinstone paints a positive picture of the forest in the North but then lets the reader imagine what the forest to the South is like. Think back to the scenario of world war 2. The soldier is in the forest and using Elphinstone’s technique, they could say something like: ‘The North side of the barbed wire was safe. The animals went about their daily business, birds were in the trees feeding worms to their chicks, fox cubs frolicked in the long grass of the clearing and a few of us managed to take off our boots and clean ourselves in the babbling brook. But on the other side of the barbed wire? Well that was another place altogether, from what he had heard it was worse than hell, a mud filled hell…’ The Lie Tree Faith walked through a midnight forest. The trees were pure white, and rose high above her head, disappearing into a blue-black darkness. There was no wind, and yet the snow-white leaves shivered and whispered. She raised one hand to push aside low-hanging foliage, and felt her fingertips brush paper. The trees were flat and pale. The ragged-torn ferns stroked the skin of her hands, paper-cutting her, slyly cruel. She was not alone. Hardinge, Frances. The Lie Tree (pp. 234-235). Pan Macmillan. Kindle Edition. The colours that Hardinge uses here are interesting and the last line. 'She was not alone' could be utilised in the scenario above to describe the soldier as well as in many other narrative scenarios. The Spell Thief (Little Legends Book 1) The air in the dark woods was thick and damp. Anansi stopped in front of a fallen tree. The roots rose above him like huge dead claws. Percival, Tom. The Spell Thief (Little Legends Book 1) (pp. 41-42). Pan Macmillan. Kindle Edition. This is a great example of simile, but it is from a book that most teachers would use with Year 3 and Year 4. Having a knowledge of books from other year groups and other key stages, including books for adults is also useful. I am working on collecting some texts around a number of themes like these which I will continue to blog and discuss in my CPD sessions. I am currently updating my CPD courses and the range which I offer for the next academic year so keep your eyes peeled for updates here www.literacyshed.com/cpd

Click the book covers for more information about each

About 3 years ago I decided to write a novel. A historical novel for children set in and around Norwich Cathedral. At this point you may be wondering 'Why?' There are a number of reasons but basically I had an idea and I fancied pursuing it. I have some time on my hands, it is purely for my own pleasure and it allows me time to drop out of the hectic day to day running of The Literacy Shed and sit quietly. It also allows me to visit as many cathedrals as I possibly can which is a secondary pleasurable benefit.

These are some of the key points that I have learned during the VERY slow process. - No one needs to read this writing in order for the process to be enjoyable. - Not everything that I write will be published anywhere except in my own private notebooks. - Not everything will go as planned because ideas ebb and flow as the ink runs across the page. - There is no need to stick rigidly to planned structures at the sentence level either. They are fluid and will change through the process. - The quality of the writing isn't dependable on a narrow set of grammatical conditions. - It is useful to write in small chunks and add them into the narrative. - Characters come alive once the writing begins and take on a whole new personality sometimes. The biggest lesson really is that it is OK to start again. The story has been set in Middles ages Norwich, which at one point became the fantasy city of Nearwich. I experimented with the same story being set during the industrial revolution and then in a strange 'steam-punkish' industrial/medieval landscape and now me and Tom (main character) are back in the medieval period. How does this affect the teaching of writing? - Remind the children that their writing may not be published but give them the choice whether to have people read it or not. - If you have a great idea you do not need to stick to the plan. - Experiment with language and grammar structure and go with what sounds best. - Write in small chunks and build up towards a finished piece. - Allow time to go back and add in more small chunks (or even big chunks) into the narrative. - It is ok to start again! Writing like this has really given me an insight in both the processes we force the children to go through and the way in which we help them to build narratives around given characters and themes. I will continue to reflect upon this process and blog about how this can aid the teaching of writing. WICKED, the award-winning West End musical that tells the incredible untold story of the witches of Oz, together with the National Literacy Trust celebrates its eighth year of the prestigious WICKED YOUNG WRITER AWARDS. As in previous years, entrants can enter one of five different age categories; 5-7, 8-10, 11-14, 15-17, 18-25. In addition, the 2018 Awards see the third year of the FOR GOOD Award for Non-Fiction, encouraging 15-25 year olds to write essays or articles that recognise the positive impact that people can have on each other, their communities and the world we live in. The WICKED FOR GOOD programme supports the charitable causes at the heart of the stage musical.

There is a 750-word limit (not including the title words) on any theme. In the fiction categories, any creative writing will be accepted, a story, play or poem, it can be something written at school or home that has not be entered into a competition before. If you prefer to write non-fiction, you may like to enter the Wicked: For Good Award for Non-Fiction and write an article, essay, biography, review or letter, to name a few! A shortlist of 120 entrants from across the UK will see their work published in the WICKED YOUNG WRITER AWARDS Anthology. They are also invited to an exclusive ceremony at London’s Apollo Victoria, home to the hit musical since 2006, where judges and members of the WICKED cast will read the winning stories and poems and announce who has won in each category. For T&C’s and full prize fund structure please see Wicked Young Writer Awards website. www.wickedyoungwriterawards.com Here are the rules: · Entrants must be aged between 5-25 years old when entering the Wicked Young Writer Awards · Entries can be hand-written or typed · Writing must be original and your own ideas · Judges criteria: originality, narrative, descriptive language, characterisation. · Ensure that all students include their name, surname and age on the entry form · Open to UK residents only All winners: · Win four tickets to see the London production of WICKED at the Apollo Victoria Theatre. · Meet cast members after the show along with an exclusive backstage tour. · £50 worth of books/eBooks tokens to spend. Other prizes for each category: 5-7 also win: · A creative writing workshop for your class · £100 worth of books for the winners' school library donated by Hachette Children's Books. 8-10 and 11-14 also win: · An annual subscription to First News · £100 worth of books for the winners' school library donated by Hachette Children's Books. 15-17 also win: · A writing masterclass with a professional author 18-25 also win: · A self-publishing package from Spiderwize, to publish your very own work. Award for Non-Fiction also win: · Work experience at First News newspaper, shadowing the editor Nicky Cox, MBE. · The 3 schools that submit the most entries also win creative writing workshops. · All finalists’ entries get printed in the Wicked Young Writer Awards anthology.

Collective Nouns

This week I came across a collective noun that I had not heard before, ‘A flamboyance of flamingos’ and this reminded me of some of others which I already knew: a business of ferrets, a murder of crows and a parliament of owls. I then started to share them each day on twitter using the hashtag #collectivenouns and sharing the most unusual examples that I could find, such as a dazzle of zebras. The posts garnered lots of interest, so I began to think about how I would use the collective nouns in writing. Many of the words are incredibly descriptive and could be used when writing setting descriptions in order to help convey a mood. For example, when creating a peaceful mood, perhaps to describe a quiet country walk, the following examples could be used: As I crossed the dew-kissed meadow, the sun rose above the distant hills and a wisp of snipe took flight from the long reeds. The word ‘wisp’ used here adds to the peaceful mood whereas an example such as a ‘pandemonium of parrots’ or ‘a band of plovers,’ or even a ‘parliament of owls’ would shatter the peace. It isn’t only birds that can lead us to imagine a peaceful moment. Barely a sound could be heard, except the gentle ruffling of the breeze-blown leaves in the trees and a prickle of hedgehogs snuffling for worms. As well as peace, they could help children to include some atmospheric language in their writing: A murder of crows nestled on the black, skeletal branches above, almost invisible now as the darkness descended. The word murder will have connotations for the reader as will the word skulk in the following example: A skulk of foxes prowled through the town, silently illuminated only by the weak moonlight. Taking it further...To take it further, collective noun can be used as similes – see the examples below: The gang prowled the estate like an ambush of tigers. The snowy mountains nestled together on the horizon like a giant aurora of polar bears. The models took to the catwalk like an flamboyance of flamingos; tall, thin and colourful. The children alighted the bus like a troop of monkeys Another interesting activity would be to ask children to create their own collective nouns. We asked on social media for a collective noun for teachers and amongst my favourites were:

As always thanks for reading! Please share!

Thanks Rob Today I had the pleasure of delivering a keynote at a conference in Wolverhampton today alongside some great speakers and the team from Wolverhampton LEA. One thing I will take away is using technology to aid spelling in writing. Mark Smith and others demonstrated how Siri can be used to aid those children whose spelling problems stop them from using a dictionary properly. His example was with children looking up 'mystery' in the dictionary by searching in the m-i-s- section and being unable to find the word they want. Here is a video of Noah in Y2 asking Siri to spell 'Caterpillar' for him: As you can see in the video as well as displaying the written spelling it also reads the spelling to the child. We then tried it with a homophone 'allowed' with mixed results. There is also an option on Google Search using the microphone button there. Here is what happened:

So as you can see it may be that homophones confuse the situation, but it could still be a useful tool for some children. We were advised today that if this is normal classroom practice that STA will accept it as independent writing for assessment purposes. (when used for single words and not whole sentences) Even if you do not think you would like to use it in independent writing it could be useful for novice writers in other year groups who can write but struggle with spelling. Comments welcome as ever. Rob  “Don’t tell me the moon is shining; show me the glint of light on broken glass.” Anton Chekov talking about the use of a well know literary device called ‘Show, don’t tell’ and more recently ‘Show, not tell.’ This method which has many proponents in the world of literature is not a new phenomenon. Ernest Hemingway opens his novel ‘To have and have not’ written in 1937 with the following lines: You know how it is there early in the morning in Havana with the bums still asleep against the walls of the buildings; before even the ice wagons come by with ice for the bars? Here Hemingway is painting a picture of early morning in Cuba, he could have easily written ‘One very early morning…’ some writers may argue that these examples are still ‘telling’ although somewhat elaborately. Calling it ‘Show, not tell though does simplify it for our students and is a great way of getting them to use vivid description. Evan Marshall from http://themarshallplan.net/ says: Don’t just write “The subway station was shabby.” Write: “Near the edge of the platform, a man with knotted hair held out a Dixie cup to no one in particular, calling, ‘Spare some change? Spare some change?’ Swirls of iridescent orange graffiti covered the Canal Street sign. The whole place smelled of urine and potato chips.” Perhaps both are telling but one is telling in much more detail. The latter has much more detail and drama. I use film widely in my teaching and I use film to demonstrate this technique. The following two extracts are from a music video called 'Titanium' by David Guetta.

These two excerpts are from one of my favourite films on The Literacy Shed, called 'Catch a Lot.'

There are many other examples in the films on www.literacyshed.com and I may follow this blog up with them if people think it is useful. Thanks for reading and I hope you leave a comment. Rob If you and I were to read a description of a setting or a character in a book then we would both come up with a different image in our heads. If I asked you to write a description then it would be that image in your head which you then transfer to the page. As adults, with a wide ranging life experience, it is relatively easy to form an image in our heads. This image may be based on real life experiences or virtual experiences from film or other images we have seen.

|

Archives

July 2020

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed