|

Planning to look at vocabulary in a reading session should not be a laborious task. A quick annotation of the text should allow you to choose the key vocabulary that you would like to look at and discuss with the students.

This week I looked at Survivors by David Long with a group of Y6 children. I decided to focus on vocabulary with the children in this short 15-20 minute reading session. The class theme at the moment is Mountains so I chose the text to tie in with this.

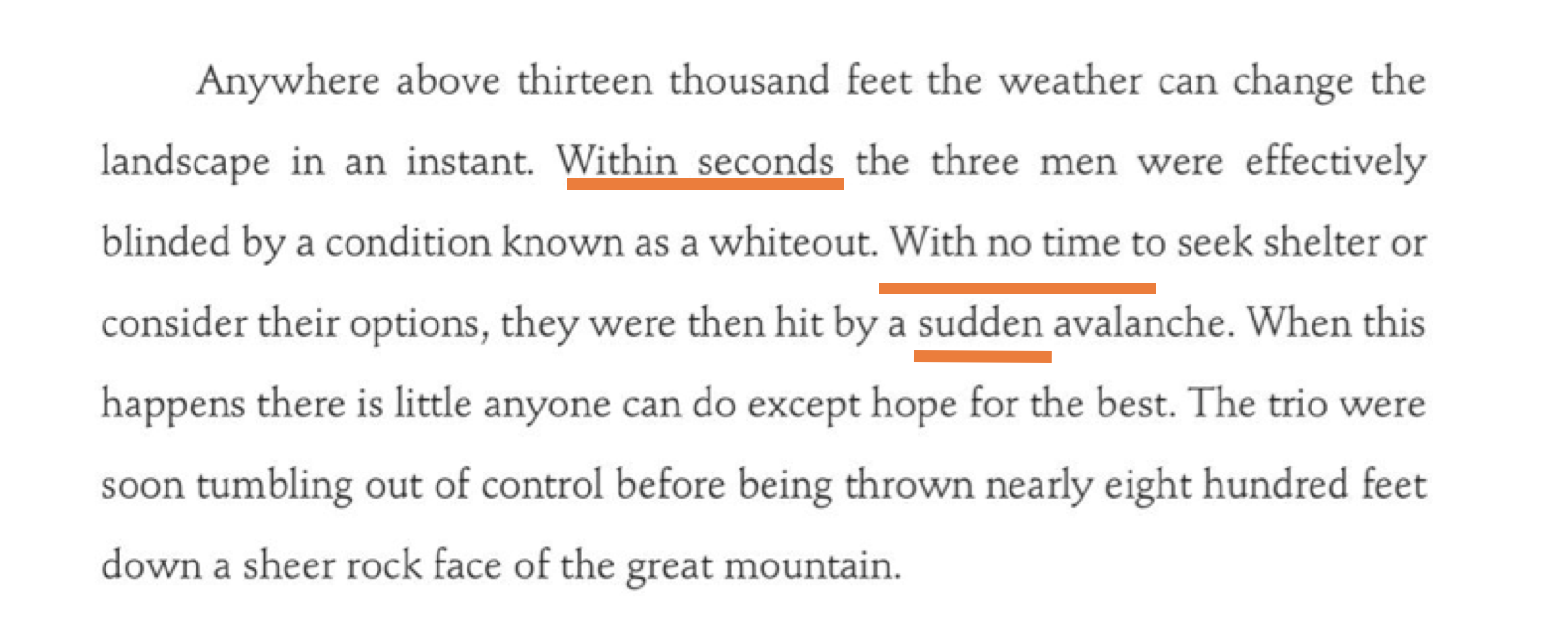

I asked – was this avalanche expected? They answered no.

I asked them to highlight or underline three phrases which show that the events happened quickly or rapidly.

They underlined: ‘Within seconds,’ ‘With no time,’ ‘sudden’ and we discussed how using all three of these in quick succession intensified the feeling of speed.

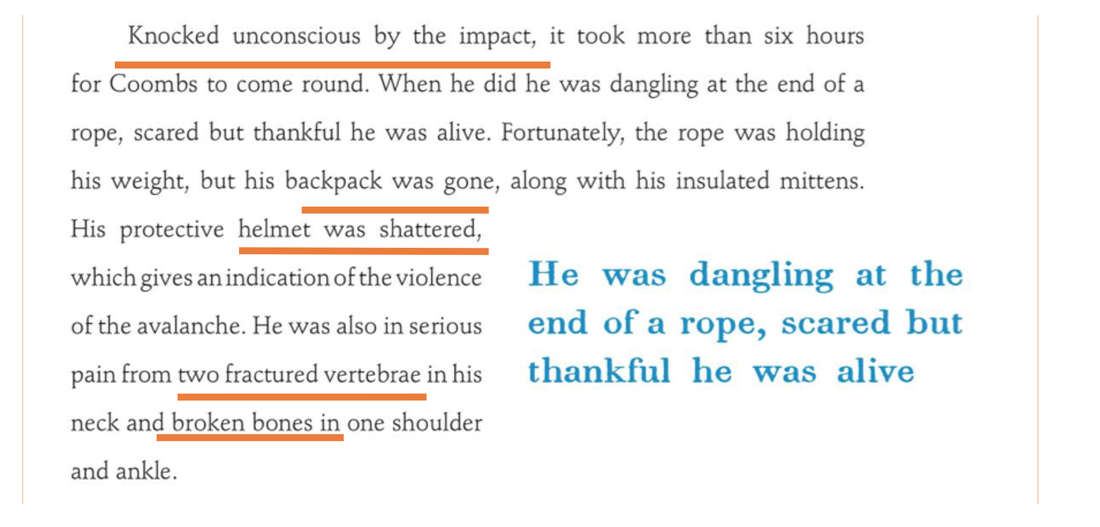

We read the next section and I instructed the students to find any evidence that the avalanche was very powerful.

We then collected synonyms that the children knew could be used to describe the powerful avalanche.

e.g. ferocious strong fearsome vicious savage awesome We then discussed which other natural phenomena could be described using these words. The savage ocean, a ferocious earthquake, an awesome eruption (of a volcano)

216 Comments

Ask a teacher to name a book about WW2 and they can usually throw around the names of quite a few. ‘The Silver Sword’ (classic one), ‘Good Night Mr. Tom’ (Heart-warming one), ‘Boy in the Striped Pyjamas’ (shocking one) and ‘Once’ (graphic one). Ask though, which of these books describes the setting of a bomb crater the best and less books may be suggested.

It is imperative though, that teachers have a good working knowledge of the texts, the language used and the structures in order to weave them skilfully into English lessons. For this to happen, a wide range of texts need to have been read by the teacher or teachers so that they can recall features, concepts and even sentences which they can use with their students as model texts. Take the examples below, each of them is from a different text but each of them describes a forest. It doesn’t really matter what genre the children are writing; a good description can be utilised across a range of writing episodes. In a hypothetical classroom, somewhere around Year 5 or Year 6, a child is writing about ‘waiting in a forest ready to go into battle during WW2’ based on a picture, film or other stimulus that the teacher has provided. If the class teacher wants to show them a model, they generally have two options – try and find a book where the exact same scenario is occurring (this may not even exist) or write their own model. (Some teachers find difficult). However, much of the language used in the extracts below would be useful, as would some of the sentence structures and techniques such as building atmosphere or using similes. None of the books below are about World War 2 or are from battle scenes though. With some slight adjustments they can be adapted to work for any narrative which needs a description of a forest. The Wizards of Once Perhaps you feel that you know what a dark forest looks like. Well, I can tell you right now that you don’t. These were forests darker than you would believe possible, darker than inkspots, darker than midnight, darker than space itself, and as twisted and as tangled as a Witch’s heart. They were what is now known as wildwoods, and they stretched as far in every direction as you can possibly imagine, only stopping when they reached a sea. Cowell, Cressida. The Wizards of Once: Book 1 (Kindle Locations 32-35). Hachette Children's Group. Kindle Edition. In this description the teacher can discuss how Cowell has directly addressed the reader, used rhetorical devices and repeated the word darker and how this effects the audience. The Dreamsnatcher Tanglefern Forest was vast, with some trees so old and tangled that few had passed beneath their branches. But there were places you went and places you didn’t. The Ancientwood in the north of the forest was safe: there was the glade of brilliant spring bluebells and yews beyond Oak’s camp, then a grove of crab-apple trees, and beyond that, after the forest, the farm itself and Tipplebury village. But south . . . Well, south was another place altogether. So she’d heard. The Deepwood was rumoured to be full of shady trees and rotting undergrowth and, when it ended, the heathland, with it sinking bogs and soggy marshes, began. Elphinstone, Abi. The Dreamsnatcher (Dreamsnatcher 1) (pp. 9-10). Simon & Schuster UK. Kindle Edition. I like in this extract how Elphinstone paints a positive picture of the forest in the North but then lets the reader imagine what the forest to the South is like. Think back to the scenario of world war 2. The soldier is in the forest and using Elphinstone’s technique, they could say something like: ‘The North side of the barbed wire was safe. The animals went about their daily business, birds were in the trees feeding worms to their chicks, fox cubs frolicked in the long grass of the clearing and a few of us managed to take off our boots and clean ourselves in the babbling brook. But on the other side of the barbed wire? Well that was another place altogether, from what he had heard it was worse than hell, a mud filled hell…’ The Lie Tree Faith walked through a midnight forest. The trees were pure white, and rose high above her head, disappearing into a blue-black darkness. There was no wind, and yet the snow-white leaves shivered and whispered. She raised one hand to push aside low-hanging foliage, and felt her fingertips brush paper. The trees were flat and pale. The ragged-torn ferns stroked the skin of her hands, paper-cutting her, slyly cruel. She was not alone. Hardinge, Frances. The Lie Tree (pp. 234-235). Pan Macmillan. Kindle Edition. The colours that Hardinge uses here are interesting and the last line. 'She was not alone' could be utilised in the scenario above to describe the soldier as well as in many other narrative scenarios. The Spell Thief (Little Legends Book 1) The air in the dark woods was thick and damp. Anansi stopped in front of a fallen tree. The roots rose above him like huge dead claws. Percival, Tom. The Spell Thief (Little Legends Book 1) (pp. 41-42). Pan Macmillan. Kindle Edition. This is a great example of simile, but it is from a book that most teachers would use with Year 3 and Year 4. Having a knowledge of books from other year groups and other key stages, including books for adults is also useful. I am working on collecting some texts around a number of themes like these which I will continue to blog and discuss in my CPD sessions. I am currently updating my CPD courses and the range which I offer for the next academic year so keep your eyes peeled for updates here www.literacyshed.com/cpd

Click the book covers for more information about each

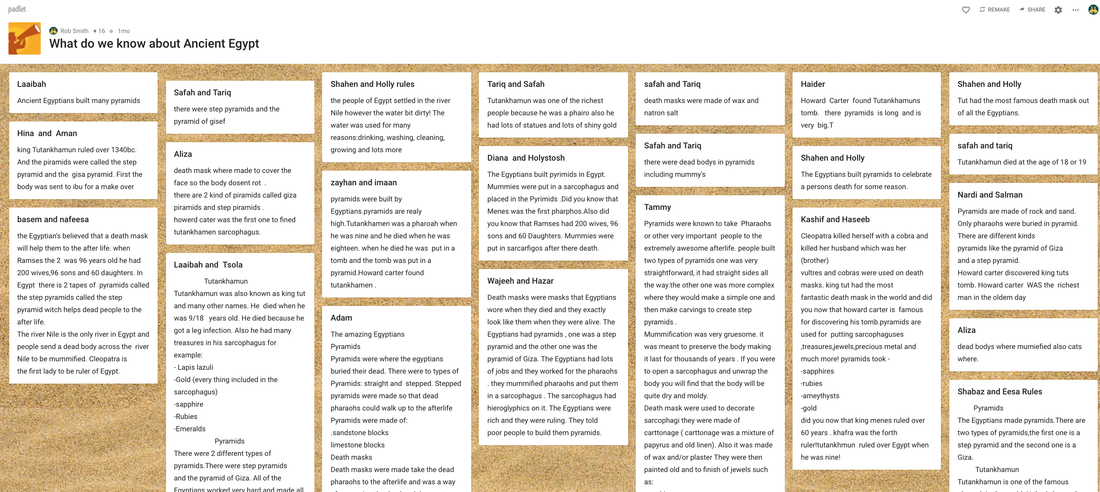

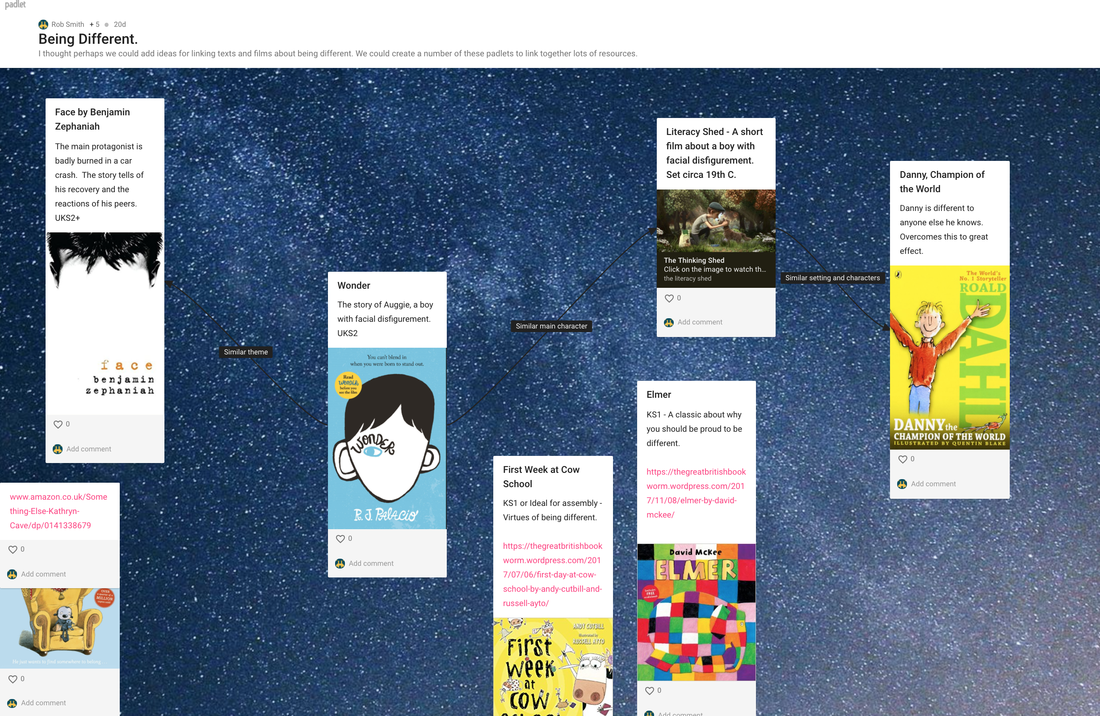

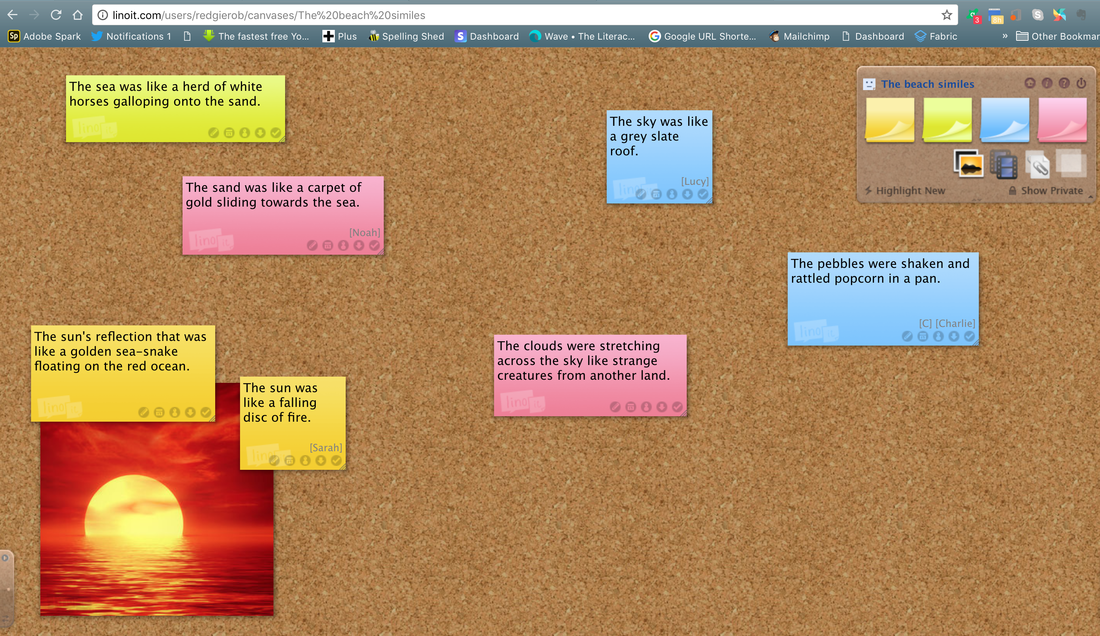

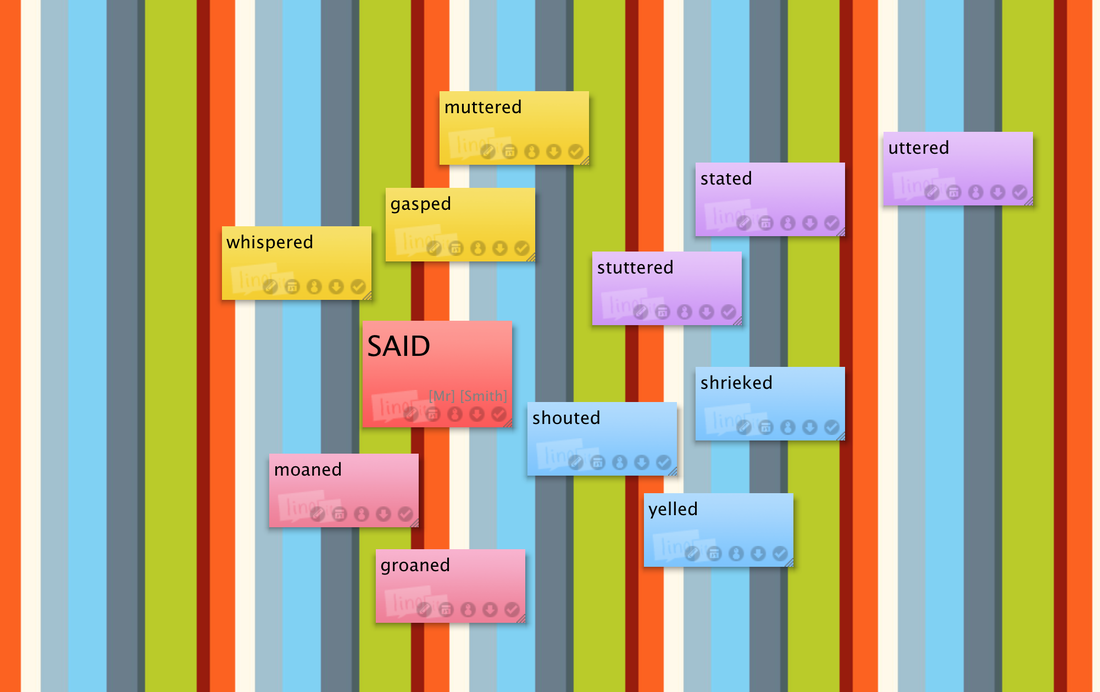

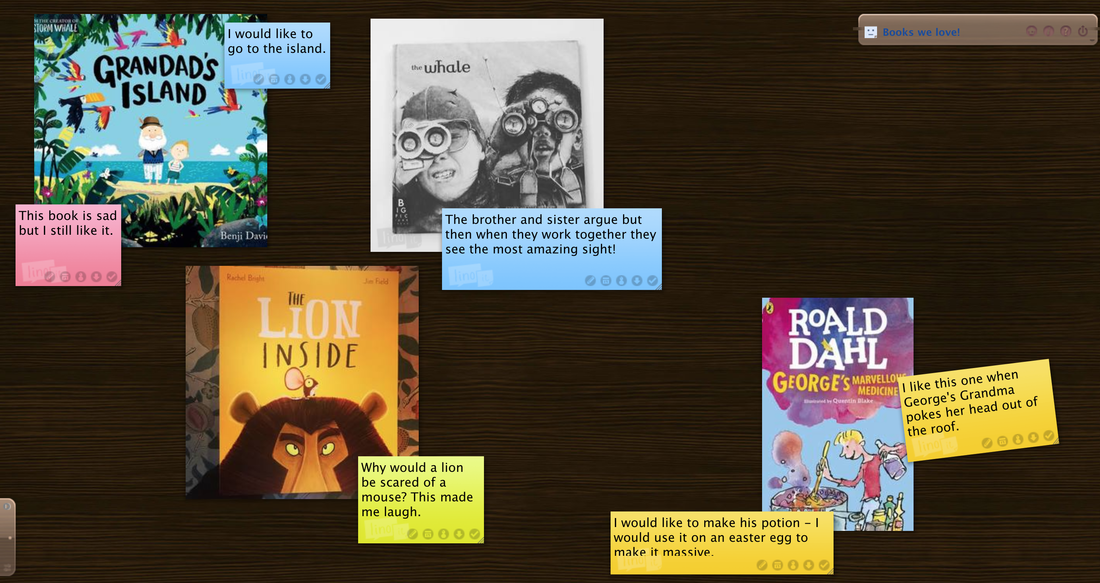

Sharing language and ideas for writing across the classroom is a valuable classroom activity. It may be when thinking of specific sentence structures; ideas for narrative content or new vocabulary. I often use Post-it notes and add these to my working walls but these are temporary and can not always be easily accessed by all pupils especially if there are groups working in different areas. In schools that have mobile devices, iPads, other tablets or laptops, I have been using www.padlet.com to allow children to share their ideas online. This can be accessed in different areas around the school, at home and it can be recalled when common learning is taking place. Examples below show that padlets can include text, image and video. They look fantastic and this collaborative learning can be sent directly to a class blog and social media streams. A great way of sharing ideas with parents. Unfortunately, Padlet have decided to start charging for the service. $99 USD for a class teacher or $1499USD for a whole school account. In this climate of ever decreasing budgets, Padlet may have just become prohibitively expensive for many teachers and schools. One alternative that I have been experimenting with is Lino. (click to visit the website) Lino is free to sign up to and works under the same premise as Padlet. Any one with the web address of a 'lino board' can post 'stickies' onto the page. You can see from the examples below that children can share their ideas in a similar way to padlet. Students can add their names to their posts, they can choose the colour of their sticky and add images and films. OVERALL: Lino does not look as good as padlet and it lacks some of the more advanced features such as profanity filter and QR code access etc but it does the basic job of sharing, storing, displaying and accessing collaborative work very well. Similes to describe the beach Thinking about words that can be used instead of 'said'. Reviewing books from the class library.

About 3 years ago I decided to write a novel. A historical novel for children set in and around Norwich Cathedral. At this point you may be wondering 'Why?' There are a number of reasons but basically I had an idea and I fancied pursuing it. I have some time on my hands, it is purely for my own pleasure and it allows me time to drop out of the hectic day to day running of The Literacy Shed and sit quietly. It also allows me to visit as many cathedrals as I possibly can which is a secondary pleasurable benefit.

These are some of the key points that I have learned during the VERY slow process. - No one needs to read this writing in order for the process to be enjoyable. - Not everything that I write will be published anywhere except in my own private notebooks. - Not everything will go as planned because ideas ebb and flow as the ink runs across the page. - There is no need to stick rigidly to planned structures at the sentence level either. They are fluid and will change through the process. - The quality of the writing isn't dependable on a narrow set of grammatical conditions. - It is useful to write in small chunks and add them into the narrative. - Characters come alive once the writing begins and take on a whole new personality sometimes. The biggest lesson really is that it is OK to start again. The story has been set in Middles ages Norwich, which at one point became the fantasy city of Nearwich. I experimented with the same story being set during the industrial revolution and then in a strange 'steam-punkish' industrial/medieval landscape and now me and Tom (main character) are back in the medieval period. How does this affect the teaching of writing? - Remind the children that their writing may not be published but give them the choice whether to have people read it or not. - If you have a great idea you do not need to stick to the plan. - Experiment with language and grammar structure and go with what sounds best. - Write in small chunks and build up towards a finished piece. - Allow time to go back and add in more small chunks (or even big chunks) into the narrative. - It is ok to start again! Writing like this has really given me an insight in both the processes we force the children to go through and the way in which we help them to build narratives around given characters and themes. I will continue to reflect upon this process and blog about how this can aid the teaching of writing. WICKED, the award-winning West End musical that tells the incredible untold story of the witches of Oz, together with the National Literacy Trust celebrates its eighth year of the prestigious WICKED YOUNG WRITER AWARDS. As in previous years, entrants can enter one of five different age categories; 5-7, 8-10, 11-14, 15-17, 18-25. In addition, the 2018 Awards see the third year of the FOR GOOD Award for Non-Fiction, encouraging 15-25 year olds to write essays or articles that recognise the positive impact that people can have on each other, their communities and the world we live in. The WICKED FOR GOOD programme supports the charitable causes at the heart of the stage musical.

There is a 750-word limit (not including the title words) on any theme. In the fiction categories, any creative writing will be accepted, a story, play or poem, it can be something written at school or home that has not be entered into a competition before. If you prefer to write non-fiction, you may like to enter the Wicked: For Good Award for Non-Fiction and write an article, essay, biography, review or letter, to name a few! A shortlist of 120 entrants from across the UK will see their work published in the WICKED YOUNG WRITER AWARDS Anthology. They are also invited to an exclusive ceremony at London’s Apollo Victoria, home to the hit musical since 2006, where judges and members of the WICKED cast will read the winning stories and poems and announce who has won in each category. For T&C’s and full prize fund structure please see Wicked Young Writer Awards website. www.wickedyoungwriterawards.com Here are the rules: · Entrants must be aged between 5-25 years old when entering the Wicked Young Writer Awards · Entries can be hand-written or typed · Writing must be original and your own ideas · Judges criteria: originality, narrative, descriptive language, characterisation. · Ensure that all students include their name, surname and age on the entry form · Open to UK residents only All winners: · Win four tickets to see the London production of WICKED at the Apollo Victoria Theatre. · Meet cast members after the show along with an exclusive backstage tour. · £50 worth of books/eBooks tokens to spend. Other prizes for each category: 5-7 also win: · A creative writing workshop for your class · £100 worth of books for the winners' school library donated by Hachette Children's Books. 8-10 and 11-14 also win: · An annual subscription to First News · £100 worth of books for the winners' school library donated by Hachette Children's Books. 15-17 also win: · A writing masterclass with a professional author 18-25 also win: · A self-publishing package from Spiderwize, to publish your very own work. Award for Non-Fiction also win: · Work experience at First News newspaper, shadowing the editor Nicky Cox, MBE. · The 3 schools that submit the most entries also win creative writing workshops. · All finalists’ entries get printed in the Wicked Young Writer Awards anthology. It is that time of year when we start to reflect on the year that has passed, Sky Sports show 100 greatest goals and Sunday supplements run their Top 10 list of stuff! I am going to share my Top 10 books of 2017; however, not all of these books were first published in 2017, but I first read them this year. Some people would have called this blog Top 10 Children's books of the year, but these books are not just for children. I have enjoyed them as much as I have 'books for adults.' If I was to add an 'adult book' to this list, then it would be A column of fire by Ken Follett. The list below is in no particular order. (Click the book covers for additional details)

The first time I saw this book it was being read on Cbeebies story time and at the end my little boy asked why my eyes were wet. Syd and his Grandad are best friends. Their houses face each other and they go on adventures in Grandad's attic. One day they go to a magical island but this time Syd returns home alone and his Grandad stays there. The next day, Syd returns to his Grandad's attic alone and feels lonely until a bird arrives, tapping on his window with a message from his Grandad. Younger children will take the story at face value but older children will understand the allegorical message.

The book consists of 'spell poems' which, when read aloud, will summon the missing language for children. The copy in our house has been pored over again and again and again by a 'nature mad' 7- year-old. The Observer sums it up quite eloquently "Sumptuous...a book combining meticulous wordcraft with exquisite illustrations deftly restores language describing the natural world to the children's lexicon... The Lost Words is a beautiful book and an important one." Do you have a favourite book that you have read for the first time in 2017? Please share them in the comments below.

As always, thanks for reading! Rob

Collective Nouns

This week I came across a collective noun that I had not heard before, ‘A flamboyance of flamingos’ and this reminded me of some of others which I already knew: a business of ferrets, a murder of crows and a parliament of owls. I then started to share them each day on twitter using the hashtag #collectivenouns and sharing the most unusual examples that I could find, such as a dazzle of zebras. The posts garnered lots of interest, so I began to think about how I would use the collective nouns in writing. Many of the words are incredibly descriptive and could be used when writing setting descriptions in order to help convey a mood. For example, when creating a peaceful mood, perhaps to describe a quiet country walk, the following examples could be used: As I crossed the dew-kissed meadow, the sun rose above the distant hills and a wisp of snipe took flight from the long reeds. The word ‘wisp’ used here adds to the peaceful mood whereas an example such as a ‘pandemonium of parrots’ or ‘a band of plovers,’ or even a ‘parliament of owls’ would shatter the peace. It isn’t only birds that can lead us to imagine a peaceful moment. Barely a sound could be heard, except the gentle ruffling of the breeze-blown leaves in the trees and a prickle of hedgehogs snuffling for worms. As well as peace, they could help children to include some atmospheric language in their writing: A murder of crows nestled on the black, skeletal branches above, almost invisible now as the darkness descended. The word murder will have connotations for the reader as will the word skulk in the following example: A skulk of foxes prowled through the town, silently illuminated only by the weak moonlight. Taking it further...To take it further, collective noun can be used as similes – see the examples below: The gang prowled the estate like an ambush of tigers. The snowy mountains nestled together on the horizon like a giant aurora of polar bears. The models took to the catwalk like an flamboyance of flamingos; tall, thin and colourful. The children alighted the bus like a troop of monkeys Another interesting activity would be to ask children to create their own collective nouns. We asked on social media for a collective noun for teachers and amongst my favourites were:

As always thanks for reading! Please share!

Thanks Rob

I do not remember learning to read. Perhaps I always just could, or perhaps it came to me at an early age, or perhaps I enjoyed it so much that I don’t have any painful memories about it stuck in my mind.

I have some early pleasurable memories about reading. The earliest of these is of my Dad and me, sat in his bed, in our pyjamas. His were chocolate brown with a yellow pocket; mine were blue striped (it was 1986). My brother had been in an accident and so my Mum was at the hospital with him. I remember we read a book about fireworks but I sadly cannot remember the title. My second earliest reading memory is the night I learned to read silently. You may think it odd that someone can remember the exact moment that they learned to read silently, but mine was almost an epiphany and the memory is just as vivid 28 years later. I don’t really like hospitals and the 7-year-old me liked them even less. There I was – facing a few nights on the children’s ward at Whiston Hospital – ready to have my tonsils and adenoids removed. I had with me an array of colouring books and a few books to read. The ward lights had been dimmed and most parents had gone home as they were not allowed to stay. I switched on the metallic, angle-poise lamp above my bed and began to read by its soft glow, my bed encased on all sides by the stiff hospital curtains. I remember that I wasn’t very far through my book when someone swept the curtains aside and said, in a whispered shout, “Shut up! You are keeping my little boy awake!” then promptly disappeared. This ‘witch’ appeared from nowhere, out of the darkness, down-lit by the hospital lamp, and she scared the dickens out of me. From that point onwards I could read in my head. What a gift this was too – it meant that no one knew whether I was awake or asleep once I had been sent to bed, and as long as I had some faint illumination, then I could read and read. And I did. I devoured anything and everything I could get my hands on. I went to Smugglers Top with Julian, Dick, Anne, George and Timmy. In fact, I went to many places with these Famous 5. I read World War Two in Colour, this had belonged to my Dad, as had the Warlord, Hotspur and Victor annuals that I found under his old bed (the one I slept in most weekends between the ages of 8 and 18 years old) at my Nan’s house. Because I could read, and read well, then I enjoyed it. If I wasn’t enjoying it, then I probably would have done something else. I must have been a teacher’s dream! I read avidly and wanted to read more. I have taught children like me, those who read everything you give them and then bring in their own books to read, discuss and share. However, not everyone is like a young Rob Smith: hungry to read and able to sate that hunger easily because home life was calm, because school was enjoyable and because home was filled with books. When I look at my own children I can see this echoing down the generations. My 8-year-old could read before he started school and my two-year-old already chooses to ‘read’ books for pleasure daily. Sometimes, as teachers, we can forget that not all children have such a ‘privileged’ home life. It startles me every time I read how many children claim to have no books at home. 10% of children, according to The National Literacy Trust (NLT 2014), leave primary school without ever visiting a library or owning their own book. Now this perception may be exaggerated by some of the children, but if they only have one or two books in the home, plus their school reading book (quite possibly from a boring reading scheme if they are of lower ability), then they are, in my opinion, book poor and will often have a deficit of cultural capital. We, as teachers, have a responsibility to these children to ensure that they leave school as readers. This responsibility is twofold:

It is my belief, under the current education system, that we often put children off reading early on through formal and informal testing and I believe that this affects boys more than girls due to them often having a more competitive nature. From an early age, most teachers share wonderful books with their class. They often read to them on the carpet as a class more than once per day, although this often diminishes as they rise through school. In fact, my first ever teaching task on my first ever placement in a school was to read a book with the class. I chose The Rainbow Fish. I remember that my task was to read the book to the children, but in addition to this, I had to formulate a number of questions to ask as we read the text and then afterwards complete a follow up activity. At the point when I started asking questions and giving out follow up tasks, I probably spoilt the whole experience for some of the children. Those who were perhaps struggling with comprehending the text may have found these follow up activities disengaging and a chore. I think on occasion, when the tasks are too difficult or strenuous, then this can have a dramatic effect on some pupil’s engagement with the text. Last week, I had the privilege of attending the Norfolk Book Centre’s annual reading conference and this year their theme was ‘Reading for Pleasure.’ I arrived a day early for the conference as there was, as always, a pre-conference meal (they are very civilised in East Anglia). To my delight, I was seated two chairs away from my hero, the renowned author Frank Cottrell-Boyce, a wonderful, softly spoken scouse nun-kicker with whom I have a couple of things in common - we come from the same part of the world! We had a chat over a carvery dinner and discussed, amongst other things, my love of ‘Millions,’ my partner’s dislike of ‘Millions’ and how Frank and the team persuaded the Queen to join in the 2012 Olympic Games opening ceremony. In his keynote the following day, Frank began by regaling us with some of his early childhood memories of home, school (this is where the nun kicking came in), and reading. I did not write down copious notes as I was so enthralled, but to paraphrase him: “We make children pay for listening to us read, or reading a great book by making them do ‘stuff’ afterwards. We need space for just giving without the need for payback.” He later echoed this sentiment when he said, “A book given freely unlocks doors for children.” What could this payback that he mentioned look like? Types of payback

Think! How often do we as teachers offer reading freely without any payback? Could you offer it more often? Back to my childhood memories… why can I remember being in bed with my dad and sharing a book about Fireworks at the age of 4? Because there was no ‘payback!’ As always, I look forwards to your comments. Rob

Time to go back to school so it is probably a good time to remember this wonderful woman,Rita Pierson.

Be that teacher who...

VIPERS displays have been requested by a number of people. Click on an image to select a set of A4 printable posters. Remember - KS1 = Sequence, KS2 = Summarise Find VIPERS novel studies, comprehensions and Film VIPERS comprehensions on www.literacyshedplus.com

|

Archives

July 2020

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed